The Complementary Roles of Realists and Anti-Realists

DongWook JUNG, "The Complementary Roles of Realists and Anti-Realists", The Korean Journal for the Philosophy of Science 27(3) (2024), 35-56. [정동욱, "실재론자와 반실재론자의 상보적 역할", 『과학철학』 27(3) (2024), 35-56]

국문 초록. 이 논문에서 나는 14-17세기 실재론자들과 반실재론자들 사이의 실천적인 차이가 천문학과 역학의 발전에서 상보적인 역할을 수행했음을 보일 것이다. 첫째, 해당 시기 유럽의 전형적인 실재론자와 반실재론자―14세기의 토머스주의자(실재론) 대 유명론자(반실재론), 16세기의 코페르니쿠스(실재론) 대 도구주의 천문학자들(반실재론), 17세기의 갈릴레오(실재론) 대 그의 반대파들(반실재론)―사이에는 과학적 실천에서 분명한 차이가 있었다. 둘째, 실재론자와 반실재론자 그룹 각각의 기여는 다른 그룹에 의해 대체될 수 없었기에, 양쪽의 기여는 협동을 통해 과학의 발전을 추동했다. 추가적으로, 나는 이러한 실재론자과 반실재론자들의 상보적인 역할이 쿤식 전체론이 가진 딜레마에 대한 한 가지 해법을 제공할 수 있음을 보일 것이다.

본문

The Complementary Roles of Realists and Anti-Realists[1]

실재론자와 반실재론자의 상보적 역할

정동욱

Abstract. I will show that realists and anti-realists from the 14th to the 17th centuries had practical differences which played complementary roles in the development of astronomy and mechanics. Fisrtly, there were obvious differences in scientific practice between the Thomists (realists) vs. the nominalists (anti-realists) during the 14th century; Copernicus (a realist) vs. instrumentalist astronomers (anti-realists) during the 16th century; and Galileo (a realist) vs. his opponents (anti-realists) during the 17th century. Secondly, each epistemic group’s contributions were irreplaceable by the other, collectively fostering the advancement of science. Further, I will give a short illustrattion about how these complementary roles of realists and anti-realists offers a solution to Kuhn’s dilemma of holism.

1. Introduction

Philosophers of science have discussed scientific realism with a focus on which thesis is right and justified.[2] However, what does it mean for someone to be a realist or an anti-realist? Would there be any difference between realists and anti-realists in actual scientific practice?[3] I believe that there would be a difference. In fact, we can find an obvious difference in scientific practice between the Thomists (realists) vs. the nominalists (anti-realists) during the 14th century; Copernicus (a realist) vs. other contemporary astronomers (instrumentalists) during the 16th century; and Galileo (a realist) vs. his opponents (anti-realists) during the 17th century. In the following, I will show that adopting a realist attitude or an anti-realist attitude indeed makes a difference in scientific practice and this difference had played complementary roles in the development of astronomy and mechanics.

Further, I will try to apply the lesson from historical episodes to one philosophical problem. Thomas S. Kuhn (1987) notes that it is difficult to modify our belief system piecemeal due to the locally holistic character of our belief system. If we want to modify a part of our belief system, we must modify the related parts together. An immature idea, contradictive or incommensurable to our belief system, is hard to be accepted into our belief system, but a mature idea that could replace our belief system could not be developed without such an immature idea. How can this dilemma be resolved? I have, if not a unique solution, a solution: distinguishing differences between models and reality, which is a lesson from the anti-realist attitude. If we could distinguish between adopting a model as a fiction and adopting the model as real, we could preserve an immature idea as a fictional model and later accept the mature idea grown from the immature idea as real. Thus, modeling, if not motivated by an anti-realist attitude, can play a role in constructing, keeping, conveying, and developing an immature, critical idea. After those immature ideas have accumulated sufficiently, someone can recognize the possibility of integrating them into a complete system and accept them as true. This marks the beginning of a revolution.

I will begin by introducing the medieval scholars’ motive and practice during the 14th century.

2. Medieval Scholars’ Motive and Practice in the 14th Century Context

As universities grew during the 13th century, Aristotelian natural philosophy rapidly spread throughout Western Europe.[4] Aristotle’s growing influence sowed the seeds of suspicions and fear of Aristotelian philosophy because some elements of Aristotelian natural philosophy conflicted with Christian faith and dogma. For example:

(1) The world was eternal, which effectively denied God’s creative act. (2) An accident or property could not exist apart from a material substance, a view that clashed with the doctrine of the Eucharist… (3) The processes of nature were regular and unalterable, which eliminated miracles. (4) And, finally, the soul did not survive the body, which denied the fundamental Christian belief in the immortality of the soul (Grant 1971, p. 24).

In order to resolve this tension, teachers in the liberal arts tried to defend Aristotle’s philosophy by distinguishing the truth of natural philosophy from the truth of theology. Further, eclecticists, such as Thomas Aquinas, sought a way to reconcile natural philosophy with theology by reinterpreting them. Despite those efforts, some conservative theologians were still displeased with both attempts. After all, in 1277, the Bishop of Paris, Etienne Tenpier, forbade the 219 propositions of Aristotle’s assertions and their implications and declared that anyone who accepted even one of the propositions would be excommunicated immediately.

After the condemnation of 1277, Aristotle’s rationalistic and deterministic propositions, including “that the first cause [that is, God] could not make several worlds” (article 34) and “that God could not move the heavens [that is, the sky and therefore the world] with rectilinear motion; and the reason is that a vacuum would remain” (article 49), which were considered to constrain God’s absolute power, could no longer be endorsed publicly (Grant 1971, p. 28). Now, God could make not only several worlds but also a vacuum.

In addition, theologians, seeking to demonstrate God’s absolute power, began to criticize the foundation of Aristotle’s philosophy. According to them, Aristotelian natural philosophy only represents contingent truths, not necessary truths. For example, according to William of Ockham (ca.1280–ca.1349), an eminent philosopher-theologian who made a strong impact on nominalists, God, who has absolute power and free will “can do anything that does not involve a contradiction;” therefore, all things and events are contingent. In addition, because necessary connection between contingent things is impossible, “Aristotelian sense of definitely knowable and necessary cause-effect relationships that had been so widely and, perhaps, uncritically accepted in the thirteenth century” is also impossible. Ockham blocked any reasoning from knowledge of existing things to knowledge of transcendent things (Grant 1971, pp. 29-30). As a result, anti-realist trends, known as nominalism, spread during the 14th century.

Even though Ockham’s radical position was not embraced by every philosopher in the 14th century, the idea that explanations of physical phenomena were merely ‘saving the phenomena’ or ‘hypotheses’ became widespread. This thought encouraged scholars to imagine possibilities free from the Aristotelian (physical) necessity. “The characteristic sign of this approach was the phrase secundum imaginationem — ‘according to the imagination’” (Grant 1971, p. 34). Now, natural philosophers and theologians in the 14th century started to create several worlds and vacuum in their imaginations.

3. The Debate on the Role of Medieval Scholars in the Development of Mechanics

Pierre Duhem insisted:

if we must assign a date for the birth of modern science, we would, without doubt, choose the year 1277 when the bishop of Paris solemnly proclaimed that several worlds could exist, and that the whole of the heavens could, without contradiction, be moved with a rectilinear motion. (re-quoted in Grant 1962, p. 200, n. 8)

Duhem’s main argument was that the Condemnation of 1277 broke down the firm beliefs in the deterministic assertions within Aristotelian natural philosophy, liberated the medieval scholars from Aristotle’s cosmological and philosophical prejudices and mode of discourse, and inspired them with scientific imagination. According to Grant (1971, 1996)’s comment, Duhem rightly pointed out that nominalists including Jean Buridan (1300-1358) and Nicole Oresme (1323-1382) exercised their adventurous scientific imaginations that could be appropriated by Copernicus and Galileo.

Firstly, Buridan and Oresme discussed the possibility of the axial motion of the earth by introducing a concept similar to relative motion. While Buridan denied the possibility because of the ordinary experience of the return of an upward-shot arrow to its original place, Oresme, later, solved the possibility of the return of an upward-shot arrow to its original place in the axial motion of the earth by assuming that the air moved along with the motion of the earth, similar to the Copernicus’ argument for the earth’s motion. Oresme concluded that it was empirically and logically underdetermined whether the earth rests and the heaven moves around, or the earth rotates and the heaven rests (Grant 1971, pp. 64-68).

Secondly, Oresme also solved one of the most difficult problems, the possibility of another world identical to our world, by modifying the definitions of the terms “up,” “down,” “light,” and “heavy” and by relativizing the concept of the center of the universe (Grant 2004, pp. 405-407). According to his new hypothesis, the heavy bodies beyond our world would not fall down into our world. While our world is possibly a unique world, there could be other worlds as well. Therefore, Aristotle’s assertion that another world was impossible was no longer true.

Thirdly, many scholars in the 14th century explored the possibility of the existence of a vacuum. Aristotle’s main argument against the existence of a vacuum was as follows:

- The motion of a body is inversely propotional to its resistance.

- A body in a vacuum does not encounter any resistance.

- Therefore, a body in a vacuum would move with infinite speed.

- Therefore, a vacuum should not exist to avoid this absurd result.

Medieval scholars, who argued for the existence of a vacuum, tried to attack premise 2. They assumed that heavy elements play a role similar to motive force to fall, while light elements play a role similar to internal resistance (Grant 2004, p. 408). According to this assumption, a compound heavy body in a vacuum would not fall with infinite speed, because it would encounter some internal resistance by its light elements. Therefore, Aristotle’s assertion that a vacuum should not exist to avoid the aburd result was no longer necessarily true. This imagination about compound bodies led some philosophers, such as Thomas Bradwardine (ca.1290–1349), to an interesting conclusion that two homogeneous compound bodies could fall in a vacuum with finite and equal speed, the same conclusion in Galileo’s De Motu (1590), because two homogeneous compound bodies that contain the same ratio of heavy and light elements would have the same ratio of motive force to internal resistance (Grant 2004, p. 410).

In sum, Duhem was right that these anti-realist scholars (unintentionally) generated numerous revolutionary ideas that laid the groundwork for later scientific developments: inertia, gravitation, and finite motion in the vacuum. But his praise on the condemnation of 1277 overestimated the nominalists’ critical power. As Grant (1971) insisted, the anti-realist attitude of the nominalists was too weak-kneed to break down Aristotelian natural philosophy and replace it by a new cosmology and physics. The nominalists were satisfied to demonstrate that alternative hypotheses were equally possible, and therefore that Aristotle’s assertions were not necessarily true. In their view, Aristotle’s assertions were simply hypotheses, disprovable by experience and logic. In order to demonstrate this, the nominalists constructed alternative hypotheses that could save the ordinary phenomena and make possible what Aristotle had regarded impossible. With these works, they could not only subdue natural philosophers’ pride, but also defend faith from natural philosophers’ reason. Their works were so successful for their purpose that they did not have to develop their ideas as real solutions for real problems.

For example, Oresme, in the end, denied the rotation of the earth and returned to the traditional position that the earth rests at the center of universe on a theological ground (Grant 1971, pp. 68-69). For him, the rotation of the earth, if God wants, is possible, but the earth rests because God would not want to rotate the earth. For another example, Oresme, closing his argument for the possibility of plural worlds, said:

I conclude that God can and could in His omnipotence make another world besides this one, or several like or unlike it. Nor will Aristotle or anyone else be able to prove completely the contrary. But, of course, there has never been nor will there be more than one corporeal world. (re-quoted in Grant 2004, pp. 406-407).

Thus, he did not believe in the existence of other worlds, but only the possibility. According to Grant,

[nominalists] generated most of the interesting and potentially significant hypothetical results in cosmology and physics, especially kinematics, and might have destroyed the Aristotelian system if they had applied their results to physical reality. Instead, their stimulating ideas and concepts were offered as mere alternatives or imaginary solutions to hypothetical problems. What was required, but not forthcoming, was a potent union of new ideas that would challenge the traditional physics and cosmology – and here significant achievements were made – with the conviction, even if naïve, that knowledge of physical reality was fully attainable” (1971, pp. 88-89).

For Grant, they were Copernicus and Galileo, scientists who gave reality to the earth’s movement, that did destroy and replace Aristotle (Grant 1971, pp. 57-59, 86-90).

William Wallace (1981, pp. 303-319) argued that Duhem overlooked the fundamental difference between nominalists and revolutionists like Galileo. According to him, Galileo, who championed the scientific revolution, was influenced by the realists, including Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, rather than by nominalists. Further, he noted that the Thomists were as critical of Aristotle as the nominalists. His suggestion is helpful to temper Duhem’s excessive thesis.

However, Wallace may have overestimated the critical power of the realists, specifically, the Thomists. Before Galileo, their realism did not aim to replace but rather complete the Aristotelian system. Grant said:

Since Aristotle himself was convinced that he had arrived at a system which represented physical reality, his many followers in the thirteenth century, most notably Thomas Aquinas, were also physical realists, much like Copernicus... [but] their physical realism was, for the most part, indistinguishable from their wholehearted acceptance of Aristotle’s physics and cosmology. (1971, p. 88)

For realists, mutually contradictory theories could not be accepted as true because they believed reality was unique and its true representation had to be unique as well. Realists should reconcile novel ideas with the Aristotelian system, whereas nominalists played with imaginations free from Aristotle and produced their own novel ideas. For this reason, Bradwardine, who built the foundation of kinematics in his imagination, was indifferent to the inconsistent or heterogeneous elements in his own theory. The same held for Buridan, who built the impetus theory in his imagination. However, when Buridan tried to apply his impetus theory to physical reality, he became a relatively consistent Aristotelian (Wallace 1971, p. 22). This does not mean that realists excluded all elements inconsistent with the Aristotelian system. New ideas could be tuned with and inserted in the Aristotelian system by the Thomist commentators. Their realist works, however, aimed not to replace but to complete the Aristotelian system.

While Wallace saw the similarity between the Thomists and Galileo concerning their realism, I see a fundamental difference between their realism. It is true that Galileo was a realist, but his realism differed fundamentally from that of the Thomists. The title of his book, Dialougue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, highlights some crucial points. In the respect that he proposed an alternative system that could save the ordinary phenomena as the Aristotelian could, his approach resembled that of the nominalists in the 14th century. However, unlike the nominalists, who constructed incomplete alternatives and didn’t believe them as true, Galileo developed a complete Copernican system comparable to the Aristotelian one and finally chose one over the other. In this respect, he was a realist.

Galileo’s realism stemmed from his dedication to assembling scattered fragments of ideas and completing a new, coherent system. His commitment was driven by his conviction of the possibility of constructing a complete alternative to the Aristotelian model. Thus, Galileo’s realist attitude paradoxically emerged as a legacy of the anti-realist attitude of the nominalists.

4. The Complementary Roles of the Realists and the Anti-realists

The above historical episode demonstrates the complementary roles of the realist and anti-realist attitude in the development of mechanics. In the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, the anti-realist attitude means tolerance to inconsistency. The nominalists were tolerant of new hypotheses contradictive to the pre-existing system and indifferent in reconciling the two or selecting one. This attitude was beneficial in stimulating their imagination and creating new hypotheses free from, or even contradictive to, the pre-existing belief system. However, it deprived them of an enduring motivation to push their hypotheses forward to reality. Therefore, it prevented them from accepting new hypotheses as true, because both old and new hypotheses were mere hypotheses, not truths.

On the other hand, the realist attitude represents a driving force to complete a consistent system. Realists such as Thomas Aquinas were intolerant of inconsistencies between the old and new ideas so that they had to find a way to reconcile the two or select among them. Thus, when a pre-existing theory was well-established, realists were disposed to be conservative, even if they did not want to. However, as the pre-existing theory (the Aristotelian theory) weakened in Galileo’s time, the realist attitude could become a driving force to complete a new consistent system despite facing significant criticism. Galileo serves as a good example of this.

When the pre-existing theory weakened, anti-realists became rather conservative. In fact, Galileo faced strong anti-realist criticisms that Galileo violated the convention of the usage of hypotheses and made a logical mistake, that is, the fallacy of affirming the consequent.[5] They thought that both the Heliocentric and the Geocentric, especially Tychonic, systems could save the heaven’s phenomena (for example, Venus’s phase change) and both theories were simply hypotheses improvable by experience and logic. This usage of hypotheses was exactly the method used by the nominalists and had been considered common sense to the scholars since the Middle Ages. Galileo, however, violated the convention of this usage by insisting that one of the hypotheses was true or better than the other – this usage can be considered a primitive form of the hypothetico-deductive method (Gingerich 1982). As a result, his opponents could not accept Galileo’s reasoning.

This interpretation of the historical episode implies that the criteria of theory choice could be different based on scientists’ epistemic attitude, realist or anti-realist. One might question how anti-realists could have different criteria for theory choice compared to realists. For example, consistency seems to be a common criterion for both positions. In response to this question, I would argue that this criterion is a common criterion only if we consider a theory as an object of belief. However, for someone who sees a theory merely as an object to understand or as a calculation tool, (internal or external) consistency doesn’t need to be a important factor in their theory choice. Especially, instrumentalists do not have to consider consistency as a necessary criterion for a good theory. It is natural for scientists with different goals to have different methods and criteria.

History of astronomy provides another, but somewhat complex, example, in which different criteria for accepting theory between realists and anti-realists played complementary roles. During the Middle Ages, the prevailing astronomy was the Ptolemaic astronomy. However, it conflicted with the Aristotelian physics. Firstly, while Aristotelian system uses a concentric spheres model, the Ptolemaic uses an eccentric deferent-epicycle model. Secondly, while Aristotelian system allowed only uniform circular motion, the Ptolemaic permitted non-uniform motion. Thirdly, while the Aristotelian system was mechanical, the Ptolemaic system was mere mathematical.[6]

As a result, Aristotle’s serious followers didn’t believe the Ptolemaic astronomy as true. That is to say, they held an anti-realist view towards the Ptolemaic astronomy. Thus, there was an epistemic hierarchy of physics (philosophy) and astronomy (mathematics).[7] Even though they criticized the Ptolemaic astronomy for lacking a physical explanation, they couldn't ignore its remarkable accuracy in making predictions. Consequently, they accepted the Ptolemaic astronomy as a precise calculation tool not a true system.

On the other hand, some of late medieval scholars sought a little more realist approach to astronomy. They were piecemeal realists on astronomy. Some astronomers within the Ptolemaic tradition, including Georg Peurbach, Regiomontanus and Copernicus, tried to combine the Ptolemaic model with the Aristotelian solid spheres, while other scholars within the Aristotelian tradition, including Fracastaro and Amici, started with concentric spheres model. Copernicus’s innovations emerged from the former tradition, not the latter.

In summary, during the Middle Ages, realists and anti-realists in the astronomy played complementary roles. The anti-realist attitude towards astronomy was necessary for the survival of the Ptolemaic system during the Middle ages. Without their instrumental accepting of the Ptolemaic astronomy, the accurate system―which eventually became the starting point of the Copernican Revolution―would have been discarded due to its conflicts with the Aristotelian system. On the other hand, the realist attitude provided a crucial motive for the innovation of the Ptolemaic system. It is important to note that during the Middle Ages and Copernicus’s lifetime, astronomers’ main motivation to innovate the Ptolemaic astronomy arose from its conflicts with the Aristotelian system, not from theory-observation disagreements.[8]

Interestingly, the anti-realist attitude towards astronomy helped the dissemination of the Copernican system in the 16th century. Many contemporary astronomers, especially in Wittenberg, treated the Copernican system as a useful tool or hypothetical object for calculating the positions of the planets (Kuhn 1957; Westman 1975; Barker & Goldstein 1998). They could understand, use, transfer, and modify the Copernican system; however, they did not believe it was real. The instrumentalist tradition of astronomy in the 16th century seemed to have contributed to at least the dissemination of the Copernican system, if not the acceptance of it as true. Of course, the acceptance of this system as real required additional criteria including external consistency. Considering this, someone like Galileo, who wanted to believe it was real, should have constructed a new kinematics consistent with it. All the 16th and 17th astronomers and scholars, including Galileo, recognized very well the heavy burdens for believing it as real, such as an inconsistency problem with the Aristotelian physics and cosmology.

5. Concluding Remarks

I showed that realists and anti-realists from the 14th to the 17th centuries had different goals and criteria which played complementary roles in the development of astronomy and mechanics. Each epistemic group’s contributions were necessary and irreplaceable by the other, collectively fostering the advancement of science. The progress in astronomy and mechanics during this period required the contributions of both groups.

I also showed that realists and anti-realists could have been either conservative or progressive, depending on the era. In the 14th century, realists (Thomists) were more conservative than anti-realists (nominalists), while in the 17th century, anti-realists (Galileo’s enemies) were more conservative than realists (Galileo and Kepler). One of the causes of this change was the decreasing power of the the Aristotelian system and the increasing hope for a new system.

Then, how did the Aristotelian system lose its power? And how could Galileo become a realist for a new emerging theory. The answers to these questions may be very complex, but from the above episodes it is natural to address one factor: the accumulation of pieces of alternative ideas to the Aristotelian system. And this answer hints a solution to Kuhn's dilemma of holism: the impossibility of peacemeal modification of our belief system.

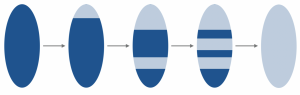

Kuhn (1987) said that it is difficult to modify our belief system piecemeal due to the locally holistic character of our belief system. If we want to modify a part of our belief system, we have to modify the related parts together. However, on the one hand, we cannot modify the whole system altogether without modifying parts piecemeal. On the other hand, piecemeal change like the diagram (Fig. 1) is impossible, because the transitional states are impossible. Then how could scientific revolutions have happened?

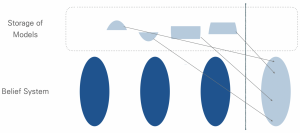

A solution to the Kuhn’s dilemma came from the complementary roles of realists and anti-realists. Firstly, some scientists, like anti-realists, can accept new ideas as fictional models not as reality. Accepting an idea as a fictional model (not as reality) lightens the heavy burden of holistic modification of our belief system. They can construct, keep, and develop several models free from their own belief system. Later, some scientists can recognize the possibility of integrating those ideas in to a complete system and accept them as true (Fig. 2). Paradoxically, their realist acceptance would result from the accumulation of fictional models and their confidence in successfully constructing a new system.

Because fictional models do not have to be a necessary part of our belief system, we can create and accumulate them in a storage outside of our belief system. In addition, a model, once constructed, can be an external object to be accessed, understood, manipulated, and modified by many people not just by individuals who believe the model is real. After all, this modeling strategy is a valuable method for constructing, keeping, conveying, and developing an immature but critical idea.

One of the fundamental sources of Kuhn’s dilemma of holism, I think, was his portrayal of scientists as uncritical children.[9] My solution to the dilemma is based on depicting scientists as adults. Unlike children, adults do not believe everything they have come to think. They can doubt something in their knowledge, construct an alternative idea, and keep it as a model for later development. In doing so, they can escape from their pre-existing belief network and keep an immature yet critical idea. Later, these ideas can be integrated into a complete whole, which can be accepted as true. This is my solution to Kuhn’s dilemma of holism.

Notes

- ↑ This paper is a revised version of the manuscript presented at APPSA 2023 in Hanoi. I am deeply grateful to the many scholars who provided valuable comments, particularly the two anonymous reviewers.

- ↑ Most scientific realists argue that the goal of science is truth and that modern mature sciences have come close to achieving this goal. However, anti-realists contend that the goal of science is not truth, and even if it were, science cannot succeed in reaching it.

- ↑ Although there is not much literature on this question, Stanford (2015) and Dellsén (2019) have discussed it. While Stanford argues that scientific realists tend to be theoretically conservative, Dellsén rejects Stanford’s argument. According to Stanford, scientific realists lack motivation to search for alternative theories because they believe existing theories are close to the truth, which means that a realist attitide is not beneficial for scientific development. I, like Stanfod, argue that realists and anti-realists have practical differences, but unlike Stanford, I acknowledge their complementary roles.

- ↑ For the general history of medieval science, see Grant (1971), Grant (1996), and Lindberg (2008).

- ↑ According to this fallacy, it is not valid to reason in the following form: A→B / B // A. From a logical standpoint, every attempt to prove a hypothesis using empirical evidences implied by the hypothesis, as in Galileo’s attempt, commits this fallacy.

- ↑ For the general history of astronomy, Hoskin (2003) and Hoskin & Gingerich (1997a; 1997b), which emphasize conflicts between the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic system.

- ↑ For the epistemic hierarchy of philosophy (physics) and mathematics (astronomy) in the medieval ages and the early modern period, see Westman (1980) and Dear (1987). In this context of epistemic hierarchy, Biagioli (1990) shows an interesting parallelism between Galileo’s transformation from a mathematician to a philosopher and Heliocentric astronomy’s transformation from a model to reality.

- ↑ See Heidelberger (1976), Gingerich (1993), and Jung & Jung (2020), which criticized Kuhn (1957; 1996)’s argument on the crisis of the Ptolemaic astronomy. For the plausible discovery process of Copernicus, see Swerdlow (1976) and Clutton-Brock (2005). They all emphasized that the astronomers’ main motive for innovation was its conflict with the Aristotelian physics.

- ↑ Kuhn (1977) stated that while learning something such as a duck, goose, or swan, the learner acquires the perception to distinguish between them and, in doing so, learns something about (the meanings and the application of) language and nature altogether (reinterpreted in Paul Hoyningen-Huene 1990). Kuhn’s remark, I think, implies that we learn the knowledge of language and the knowledge of nature simultaneously. This may be true for children’s learning. Children may not distinguish between the knowledge of language and that of nature; however, adults often, if not always, distinguish between these components of knowledge. Similarly, while students may not distinguish between the knowledge of the Newtonian model and that of nature, mature physicists can distinguish between them. Thus, Kuhn exaggerated the association between the knowledge of language and that of nature. In other words, he ignored the normal ability of distinguishing between keeping a model as a useful object and believing the model as a natural knowledge. This is why he often described normal scientists as naïve realists trapped in their paradigm while he was rather like an anti-realist free from a paradigm. This is also why normal scientists in his writings, look like children uncritical to their own knowledge. In fact, Kuhn has developed his ability to distinguish between models and reality from the history of science; however, he does not give the same ability to his normal scientists.

References

Barker, P., & Goldstein, B. R. (1998), “Realism and Instrumentalism in Sixteenth Century Astronomy: A Reappraisal”, Perspectives on Science 6, 232-258.

Biagioli, M. (1990), “Galileo the Emblem Maker” Isis 81(2), 230-258.

Clutton-Brock, M. (2005), “Copernicus’s Path to His Cosmology: An Attempted Reconstruction”, Journal for the History of Astronomy 36(2), 197-216.

Copernicus, N. (1992), On the Revolutions, translated and commentary by Edward Rosen. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dear, P. (1987), “Jesuit Mathematical Science and the Reconstitution of Experience in the Early Seventeenth Century”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 18, 133-175.

Dellsén, F. (2019), “Should Scientific Realists Embrace Theoretical Conservatism?”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 76, 30–38.

Gingerich, O. (1982), “The Galileo Affair”, Scientific American 247, 118-127.

Gingerich, O. (1993), ““Crisis” versus Aesthetic in the Copernican Revolution“, in O. Gingerich, The Eye of Heaven: Ptolemy, Copernicus, Kepler, (pp. 193-204). New York: American Institute of Physics.

Grant, E. (1962), “Late Medieval Thoughts, Copernicus, and the Scientific Revolution”, Journal of the History of the Ideas 23, 197-220.

Grant, E. (1971), Physical Science in the Middle Ages. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Grant, E. (1996), The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts, Cambridge University Press.

Grant, E. (2004), “Scientific Imagination in the Middle Ages”, Perspectives on Science 12, 394-423.

Heidelberger, M. (1976), “Some Intertheoretic Relations between Ptolemean and Copernican Astronomy”, Erkentnis 10, 323-336.

Hoskin, M. (2003), The History of Astronomy: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hoskin, M., & Gingerich, O. (1997a), “Islamic Astronomy”, in M. Hoskin (ed.), The Cambridge Illustrated History of Astronomy, (pp. 50-63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoskin, M., & Gingerich, O. (1997b), “Medieval Latin Astronomy”, in M. Hoskin (ed.), The Cambridge Illustrated History of Astronomy, (pp. 68-97). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoyningen-Huene, P. (1990), “Kuhn’s Conception of Incommensurability”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 21, 481-492.

Jung, D., & Jung, W. (2020), “Revolutions without Crisis: Focused on the Copernican Revolution”, The Korean Journal for the Philosophy of Science 23(2), 1-51.

Kuhn, T. S. (1957), The Copernican Revolution: Planetary Astronomy in the Development of Western Thought, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1977), “Second Thoughts on Paradigms”, in T. S. Kuhn (ed.), The essential tension: Selected studies in scientific tradition and change, (pp. 293-319). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1987), “What are Scientific Revolutions?”, in L. Krüger, L. J. Daston & M. Heidelberger (eds.), The Probabilistic Revolution, Vol. I, (pp. 7-22). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Lindberg, D. C. (2008), The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450, 2nd edition, University of Chicago Press.

Rosen, E. (1937), “Commentariolus of Copernicus”, Osiris 3, 123-141.

Stanford, P. K. (2015), “Catastrophism, Uniformitarianism, and a Scientific Realism Debate That Makes a Difference”, Philosophy of Science 82 (5), 867-878.

Swerdlow, N. M. (1973), “The Derivation and First Draft of Copernicus’s Planetary Theory: A Translation of the Commentariolus with Commentary”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117, 423-512.

Wallace, W. A. (1971), “Mechanics from Bradwardine to Galileo”, Journal of the History of the Ideas 32, 15-28.

Wallace, W. A. (1981), Prelude to Galileo: Essays on Medieval and Sixteenth-Century Sources of Galileo’s Thought, D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Westman, R. S. (1975), “Three Responses to the Copernican Theory: Johannes Praetorius, Tycho Brahe, and Michael Maestlin”, in R. S. Westman (ed.), The Copernican Achievement, (pp. 285-345). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Westman, R. S. (1980), “The Astronomer’s Role in the Sixteenth Century: A Preliminary Study”, History of Science 18, 105-117.

관련 항목

- 정동욱, 정원호, 위기 없는 혁명: 코페르니쿠스 혁명을 중심으로

- 쿤, 코페르니쿠스 혁명